WHAT ARE HAWAI‘I’S WATER LAWS?

Hawaiʻi water laws originate from kānāwai—traditional laws set forth by aliʻi nui (ruling chiefs) for the management and use of fresh water—which were codified in early laws of the Hawaiian Kingdom. The same rights are preserved today in the Hawaiʻi State Constitution (Article XII, Section 7 and Article XI, Sections 7 and 9 ) and Water Code (HRS Chapter 174C). These laws protect streams, ensuring that they have adequate water flowing through them to support:

- The cultivation of healthy crops, especially taro farming in loʻi

- Thriving stream life

- Thriving ocean life, which is dependent on freshwater

- Families exercising their traditional and customary rights to gather resources supported by freshwater, including resources to feed their families

- Community members’ enjoyment of stream recreation activities

- Adequate recharge of underground aquifers

- Household uses

- Beautiful, healthy environments

WHAT ARE CROWN LANDS?

In 1848 when private property land rights were established in the Hawaiian Kingdom, rights to land and its resources were divided among the monarch (King Kauikeaouli), chiefs, and hoa ʻāina (aboriginal tenants). Kauikeaouli provided a portion of his lands to establish the Hawaiian Kingdom’s Government Lands. The portion he held for himself was called Crown Lands.

Kauikeaouli passed his Crown Lands to his heir to the throne, establishing a precedent. In later years, Crown Lands were considered the personal property of the monarch. They were transferred to the next monarch upon the passing of the former. These lands were the personal family property of the ruling, related Kamehameha and Kalākaua dynasties.

At the time of the illegal overthrow in 1893, the so-called Provisional Government asserted control over the Crown and Hawaiian Kingdom Government Lands, and later, as the Republic of Hawaiʻi, transferred these to the United States. Upon statehood, a majority of those lands were transferred to the state of Hawaiʻi through the Admission Act, with the understanding that the lands would be used for public purposes, including “the betterment of the conditions of native Hawaiians.”

Through each of the different eras, traditional gathering and use rights (including water use rights) applied to all lands in Hawaiʻi.

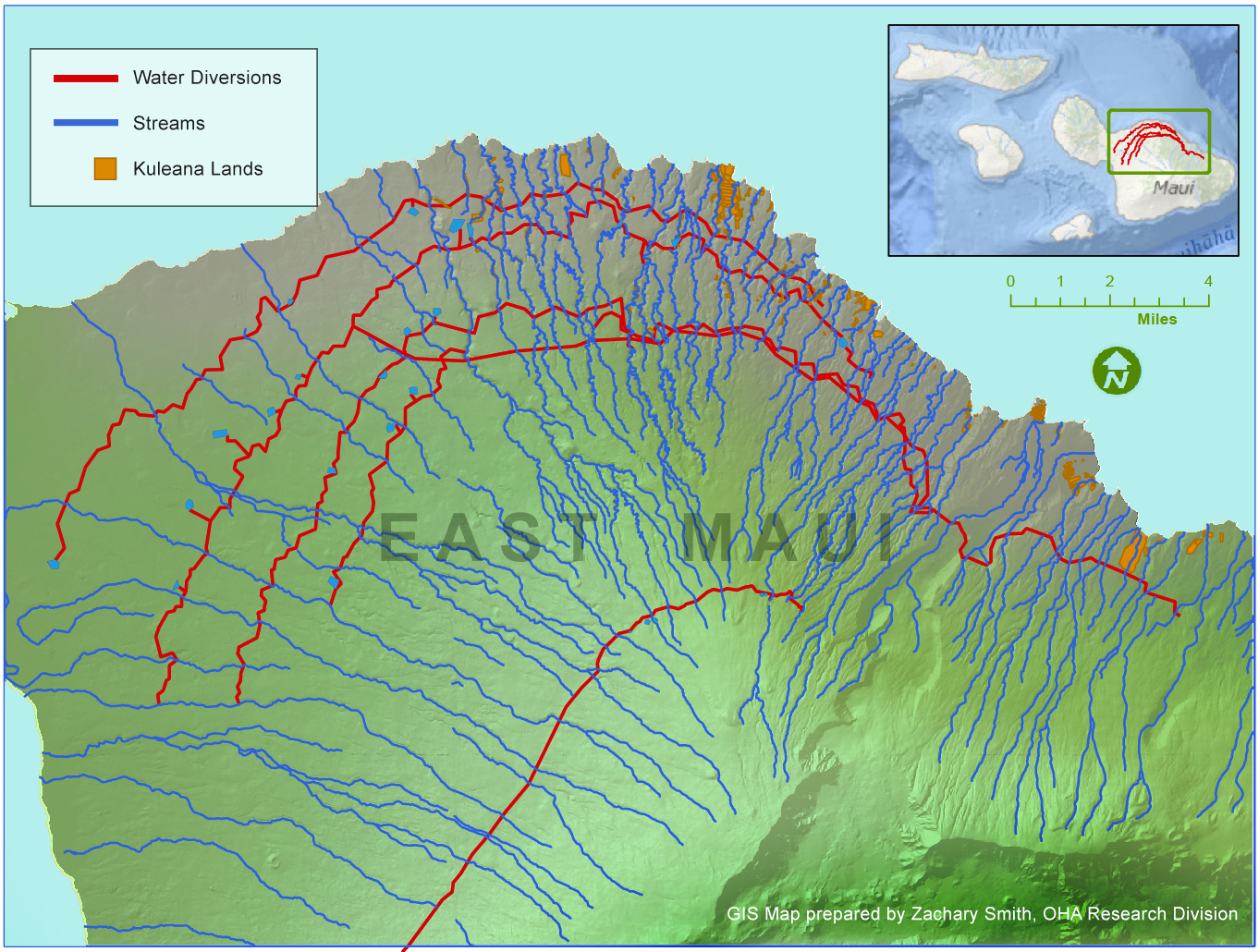

Kuleana lands, streams, and diversions shown on this map illustrate the impact that the diversions have had on hundreds of Native Hawaiian families since the early 1900s. Click to enlarge. Map by: Zachary Smith, OHA Research

Watch: Ola i ka Wai: East Maui. 4Miles, LLC for Kamakakoʻi

On March 3, 2015 the State Commission on Water Resource Management reopened a case that the court mandated it to hear nearly three years ago. It involves ʻohana from Honopou, Keʻanae and Wailuanui in East Maui who have been farming kalo for centuries and who had been raising concerns since the 1880s.

These kalo farmers are seeking enforcement of some of Hawaiʻi’s oldest laws, which define wai (water) as a public trust resource. By law, wai must be managed by the state for the benefit of its citizens, with priority given to Native Hawaiians whose activities rely on wai for traditional purposes, such as growing kalo or gathering food from streams.

Yet the state allows Alexander and Baldwin (A&B) to use 163 million gallons of wai per day (mgd) from over 100 East Maui streams. This is about the same amount of wai that all of Oʻahu uses on an average day. A&B’s subsidiary East Maui Irrigation (EMI) extracts the water, which feeds the sugar fields of A&B’s other subsidiary, Hawaiian Commercial and Sugar (HC&S).

How can wai—entrusted to the state for the benefit of all—be diverted in such enormous quantities for so long to a for-profit company?

ʻOhana from East Maui protested fearing that too much wai would be taken and their way of life threatened. They relied on wai for drinking, for nourishing kalo in their loʻi (pondfields), for plentiful stream life they gathered to feed their families (ʻoʻopu, hīhīwai, hapawai, ʻōpae), for the abundance in the muliwai (estuary areas) created by the brackish mix of wai and seawater near shore where young fish, invertebrates and native limu thrived. This near shore abundance also played a critical role in the reef and larger marine ecosystem, which fed Native Hawaiian communities both ma kai and ma uka.

Kalākaua protected the rights of these ʻohana, placing a clause in the Crown Lands leases prohibiting sugar businessmen from harming those living downstream of the diversions.

Construction of two limited ditch systems occurred in the late 1870s (the Old Hāmākua Ditch and the Spreckels Ditch). They cut across a portion of East Maui’s streams diverting water from those streams. The ditches ran parallel to the ocean and ultimately irrigated sugar plantations in Central Maui.

At the time, only a relatively small amount of wai was extracted. Life continued in East Maui much as it did for many generations.

According to Carol Wilcox (Sugar Water, Hawaiʻi’s Plantation Ditches, Table 4), the average flow of the two original ditches accounts for only a fraction of the modern total—4 mgd coming from the Old Hāmākua Ditch, with the Spreckels Ditch contributing nothing as it was abandoned by 1929.

A COLOSSAL INCREASE IN WATER DIVERSION

Despite repeated East Maui community protests of ditch building plans, sugar businessmen retained—and renewed over time—four leases from the territorial and state governments totaling some 33,000 acres of Crown Lands.

Between 1900 and 1923 six more ditches were built (Lowrie, New Hāmākua, Koʻolau, New Haʻikū, Kauhikoa, and Wailoa) on the leased land. These join to create four major water diversion pathways through East Maui that extract a vast majority of the average 163 mgd taken daily.

The early 1900s diversions impacted hundreds of East Maui ʻohana that were living on their Kuleana Lands that the Hawaiian Kingdom granted hoa ʻāina, or aboriginal tenants (see map of Kuleana Lands and diversions). These ʻohana cared for their own needs. But with massive increases in wai being diverted, East Maui communities were devastated.

Many ʻohana were forced to move out, as healthy streams became trickles, loʻi turned dry or too warm and stagnant to sustain kalo, and fish populations dwindled. Parched streambeds emerged as scarred wounds in the lush valleys of East Maui.

In areas where diversions did not take all the wai, families remained and adjusted to smaller flows—even through the 1980s. However, around that time, East Maui kalo farmers experienced further hardship as diversions siphoned still more wai.

“The politics of economics appear to trump the law”

A COMMUNITY RISES UP

Tackling the dire situation, leaders such as the late revered kupuna Harry Mitchell of Keʻanae began working with the Native Hawaiian Legal Corporation (NHLC) to take formal action. By the 1990s, kalo farmers banded together as Nā Moku Aupuni o Koʻolau Hui to continue the fight, still under the representation of NHLC, an entity funded in significant part by the Office of Hawaiian Affairs.

“I’m proud to see East Maui leaders taking charge of the situation,” said OHA Maui Trustee Carmen Hulu Lindsey. “These diversions are stripping our people of our cultural right. It pains me when I hear our kalo farmers say they have to close down their loʻi because there’s not enough water,” she added.

Led by its president, Ed Wendt, Nā Moku remains at the forefront of this struggle. “We have to stand up for our rights. It’s a huge kuleana (right and responsibility). This is considered the largest contested case in the history of Hawaiʻi nei,” says Wendt. “It’s been a long journey. But I ain’t giving in. My kūpuna would never tolerate us if we no can fight for our own backyard, no matter how long it takes,” confirmed Wendt.

“These diversions are stripping our people of our cultural right. It pains me when I hear our kalo farmers say they have to close down their loʻi because there’s not enough water”

Healoha Carmichael in the dry streambed of Honomanū where her grandparents had once taught her how to gather such food as hīhīwai and ‘o‘opu. The streams no longer run mauka to makai. The rocks are wet from the falling rain. Click to enlarge. Video still: 4 Miles LLC

YEARS OF WATER COMMISSION INACTION

In 2001, Nā Moku petitioned the Water Commission to set inflow stream standards to increase the water in the streams to fulfill the rights granted in the state constitution and Water Code. That would have required EMI to decrease its diversions.

Recognizing the steep uphill battle, Nā Moku sought partial restoration of only 27 of the more than 100 diverted East Maui streams. These were streams the community had used for gathering and farming. However, the Commission limited its consideration initially to only eight streams used for taro cultivation in this modern era.

After voluminous Nā Moku documentation and various legal proceedings, the Commission finally took action in 2008. It ordered EMI to reduce its diversions of six streams to meet interim (or provisional) instream flow standards then set, leaving two of the eight without relief. The Commission also committed to monitoring levels of the six streams as well as the taro farmers’ ability to grow crops at those levels.

If monitoring showed that EMI’s releases did not raise the levels to the interim standards, EMI would have to release more wai. If farmers were not able to grow kalo successfully with the levels set, the standards were to be increased until they were adequate.

The Commission’s staff reports in 2008 and 2009 confirmed that the interim instream flow standards were not being met, and visits with farmers revealed a lack of adequate water, including dry, cracked loʻi beds.

Following the Commission’s 2008 decision, EMI should have released more water to the six identified streams. “But EMI ignored the farmers’ plight, and the Water Commission did nothing,” said Alan Murakami, senior NHLC attorney.

Lyn Scott, a taro farmer of Honopou, recalled EMI President Garret Hew’s response to her family’s distress: “He told my mother (Marjorie Wallet) and aunt (Beatrice Kekahuna) that they should start growing kalo dryland style and invest in drip irrigation to make the water go further.”

All the while, “EMI takes out of (East Maui) 60 billion gallons of wai a year,” reminded Wendt.

“The politics of economics appear to trump the law,” said Murakami.

LO‘I IRRIGATION RETURNS WAI TO THE LAND

Kalo farming in loʻi (pondfields) is one of the most efficient methods of irrigating crops. A small portion of a stream is directed to an ʻauwai (irrigation system) that delivers fresh, cool water to a set of loʻi. The water flows in on one side of a loʻi then flows out from the lower end and into another loʻi, then another, and another, eventually returning the water to an ʻauwai, which feeds back into the same stream. All the while the loʻi, ʻauwai, and stream recharge the underground aquifer. Nutrients gained along the way through the loʻi system supercharge the stream flow, providing near shore fishes a bountiful feast that in turn provides bigger fish higher in the food chain the abundance they need for healthy populations.

BOARD GAMES AND CROWN LANDS

While petitions to the Water Commission sought managed stream protection following the Water Code, the East Maui community pressed forward on a second front: the Board of Land and Natural Resources (BLNR).

NHLC attorneys questioned the BLNR’s leases to EMI of 33,000 acres of Crown Lands, which the 1959 Admission Act (Section 5f) directed the newly established state of Hawaiʻi to use for public purposes, including “the betterment of the conditions of native Hawaiians.”

These Crown Lands, seized from Queen Liliʻuokalani during the illegal overthrow, were no longer in 30-year leases. By 1986 those had expired.

Evading public scrutiny that would have been raised by renewing a 30-year lease to a for-profit corporation, the BLNR instead issued leases for the four areas using month-to-month revocable permits, which could be extended for up to one year.

Skirting the one-year limit, the BLNR from 1986 to 2002 issued permits for the use of the 33,000 acres, alternating year to year between EMI and its parent company A&B—despite Nā Moku attempts to end the illusory practice.

By 2001 A&B/EMI requested that the BLNR issue it a full 30-year lease to use the 33,000 acres for “developing, diverting, transporting and using government-owned waters.” Nā Moku formally contested the lease request stressing that the BLNR could not issue such a lease without first completing an environmental assessment of the potential impacts of the action on East Maui communities, aquifers, and ecosystems dependent on the streams, as required by law (HRS 343-5) for any proposed use of state lands.

Following a series of legal proceedings, in 2003 Circuit Court Judge Eden Elizabeth Hifo ruled that the BLNR must conduct an environmental assessment before it considers issuing A&B/EMI the 30-year lease.

Through today the BLNR has not completed the environmental assessment. Dodging the court’s ruling, since 2003 the BLNR has leased A&B the 33,000 acres under the fabricated notion of the lease being a “holdover” of the earlier one-year revocable permit.

“A ʻholdover’ permit is supposed to last for only one year. Yet the BLNR has simply allowed the ‘holdover’ to go on for 13 years without completing an environmental assessment to determine whether such use of conservation land for water diversion is appropriate,” noted Nā Moku attorney Murakami.

“Playing with revocable and ‘holdover’ permits, A&B/EMI and the BLNR will have gamed the system for a full 30 years, at the close of this year, without undergoing the scrutiny that a valid 30-year lease would have triggered,” said Murakami.

The BLNR contends that it can continue operating in this “holdover” mode until the Water Commission sets the instream flow standards for the 27 streams that Nā Moku sought to restore in 2001.

A GREAT DEAL FOR EMI

The state Board of Land and Natural Resources permits EMI to use about 33,000 acres of land for $160,000 annually. EMI extracts via this lease, and its ditches on the land, about 163 million gallons daily (mgd) from East Maui’s streams (over 400 mgd during the rainy season). EMI’s permit fee translates to EMI paying about one-quarter of one penny per 1000 gallons of water. EMI sells water from these public lands to Maui County at a significant mark up and Maui County in the end sells it to farmers for $1.00 per 1000 gallons and to those in single-family dwellings for $1.90 per 1000 gallons.

MISSED OPPORTUNITIES

“It’s frustrating to think that A&B years ago could have pursued long-term, win-win solutions, such as reducing water wasted in their ground pumping and surface water delivery systems. A&B’s own estimates show that they lose through seepage and evaporation over 41 million gallons of water per day, which is far more than what Nā Moku is seeking for stream restoration. A&B keeps wasting water while kalo farmers suffer,” said Murakami.

“These streams and valleys were healthy,” recalled Wendt. “Since EMI took more and more water, invasive plants have come in, choked out the stream beds and spread from there. Our families have to go many more miles up ma uka and clear the streams to keep the small flows moving. I worry that these places will never be the same again.”

The court ruled that the commission failed to give proper consideration to the rights of Native Hawaiians and the public to the flowing streams. The court also ruled that the water commission needed to further explore credible alternatives to draining the streams, including perhaps eliminating inefficiencies, recycling wastewater or using non-potable wells.

In short, the court sent the case back to the water commission to redo its decision and improve its analysis of the amount of water that should be restored to the streams. While the community groups acknowledge that they are not looking to put the plantation out of business, they did stress a desire to help wring inefficiencies out of its operations.

Examples include forcing the plantation to fix leaks in dilapidated water systems and make sure they are not unnecessarily over-watering crops. “It’s now a waiting game,” said John Duey, president of the Hui o Nā Wai ‘Eha, which was formed in 2003 in direct response to concerns about diverted water from streams. “The law says what they are doing is not right; the law should be upheld. It’s time to put the water back.”

“We are not asking for special treatment. We are seeking what the law already provides.”

TIME FOR ACTION

With the contested case hearing nearing its end, the matter will shortly rest with the Water Commission’s hearing officer Lawrence Miike to recommend a decision that will affect the initially identified 8 streams and their related tributaries (Makapipi, Waiokamilo, Wailuanui, Palauhulu, Huelo, Hanehoi, Pi‘ina‘au, Kualani, Palauhulu, and Honopou) as well as the other 19 streams originally included in Nā Moku’s 2001 petition.

“We are not asking for special treatment. We are seeking what the law already provides. Nā Moku is hopeful that Hearing Officer Miike and the Water Commissioners will do what is pono—for the streams, for the places of East Maui, for our people,” said Wendt.

This article originally appeared in the April 2015 issue of Ka Wai Ola.